Jan Autengruber

Painter Jan Autengruber (b. in Pacov, Apr. 25, 1887; d. in Prague, July 15, 1920) studied at the School of Applied Arts in Prague (Prof. Emanuel Dítě, 1904-1905), and at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Munich (Prof. Hugo von Habermann; Prof. Angelo Jank, 1907-1911 studio of painting; 1915 studies of fresco painting and art restoration with Max Dorner). He spent most of his career in Munich. In 1910 he made a trip to Paris, and in the following year he won first prize awarded by the Hanover- based paints manufacturer Pelikan, for his painting The Bath II. As a Klaar scholarship recipient, he spent the years 1913-1915 in Italy. In 1917 he was drafted and sent to the war front, but was soon given a leave to do restoration work on church wall-paintings in the town of Jindřichův Hradec. After 1918 he was active in southern Bohemia and in Prague. He fell ill with the Spanish flu which ended up in a serious case of pneumonia. While in hospital, he did pencil and occasionally watercolour drawings, chiefly on themes from the Old Testament. He died at the Vinohrady Hospital in Prague, in 1920.

A chapter apart in the development of Autengrubers creative output is represented by several paintings dating from 1904, named after the location of their origin, Sázava. They relate to the patchy, expressive yet still more or less decoratively conceived brand of Post-Impressionism epitomized by the Czech painter Antonín Slavíček.

Autengrubers beginnings as a painter date bacíc to the period of the final echoes of Art Nouveau. He embraced the spectacular realism of the Munich school, initially lacing it with a tension between a naturalist idiom and impressionistic colour patches. His symbolistic portrait, Mother and Daughter (1910), most likely captures the likeness of the artisťs Munich landlady, Frau Fassnacht, with her daughter. The painting, whose concept is rather more anachronistic than modernist, tends towards chiaroscuro modelling of the figures harking bacíc to Rembrandt.

Apart from portraits painted in a relaxed manner without giving up on the element of overall descriptiveness, Autengruber evolved while in Munich to a production of monumental, half-figure or full-figure portraits of representative character, which were well tuned to the demands of his clientele. Along with the exquisite Portrait of the Violinist Adolf Hartmann- Trepka (1912), these also include the psychologically piercing Portrait of Paul Steinberg (1912). Indeed, the portrait of Hartmann-Trepka, a friend of the author Lion Feuchtwanger, has been regarded as “one of the finest portraits to have issued from the studio of a Czech painter.” (A. Birnbaumová)

Towards the end of the centurys first decade, Autengrubers style became increasingly relaxed, tending to an emphasis on expression and freedom of painterly gesture, so in that respect his output shared the same platform with the contemporary production of Lovis Corinth or Max Liebermann. Autengrubers light and crisp “painterliness” would hardly have been imaginable without the broader context of transformation which had taken place in German realistic painting during the late 19th century. It was in fact Liebermann who, through his concept of “painterly imagination,” suggested a novel approach to painterly texture and to the concept of a painting. Liebermann ushered in the term, “creative imagination,” which translated into practice as a method of active painting applicable to naturalism. In a way, what it came down to was a German variant of the “peinture pure” in French painting.

In 1912 Autengruber painted, for display at a school exhibition, a female nude group which he entitled The Bath III. It was thus far his most representative tableau: While it did comply with the academic definition of the relationship between incarnate and white colours in nude painting, the artist moreover embued it with the sum of his acquired skills and painterly talent, with a view to convincing the spectators about his capacity to produce, “on commission,” something more than just well-done craft work. The painting does not impose on the viewer the actual content of bathing and washing; indeed, nothing in its action relates to it in an explicit manner. The individual nude figures are viewed here from different angles, thus achieving a contrast with the scenes white, slightly erotically teasing drapery, to render a true embodiment of the beauty of womanhood and maternity. The nondescriptive and nonliterary nature of this type of painting - where a nude or a toilet are devoid of the narrative element - can be likened to the “absolute” experience of listening to music. Similarly elsewhere, the White Studies of the Czech painter Miloš Jiránek can be interpreted through the prism of the tendency prevailing at the time to draw parallels between colours and musical notes.

The standard teaching method at the Munich Academy involved the copying of works by the Old Masters. For his part, Autengruber did copies, at the Pinakothek, of the child figure from Jordaens' Satyr at the Peasanťs House, Antonis van Dycks Portrait of Pieter Snayers, or a fragment with putti and fleurs-de-lys from the Madonna in Floral Wreath by Pieter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder. In some cases, the artist would copy only parts of selected paintings. Particularly suggestive is his copy, from 1915, of the Apostles John and Peter, from Albrecht Durer s Four Apostles, which brings across the artisťs phenomenal talent at understanding and empathiz- ing with the “velvety” yet in condensed technique of the German Master. If one adds to those copies works which Autengruber produced in Italy, such as Mary Magdalen of 1914, his copy of Jacopo Tintorettos painting from around 1598, at the Musei Capitolini in Rome, or his copy of Botticellis Judith (c. 1470), made on April 2, 1915, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the result will be a gallery of remarkable copies which may be viewed as an attempt at appropriating the art of the Old Masters, their techniques and their creativity, which is in the final analysis not just a gesture of triumph, but also one signalling the continuity of modernism. It marks the birth of Old Master Modernism.

In 1910, Autengruber was granted a travel scholarship by the Munich Academy. He simultaneously submitted a scholarship application to the Prague Governorate. As a result, he was able to make a journey of several months, across Germany and to France. Surviving paintings and studies from the tour make possible the identification of its stages: Ulm, Stuttgart, Strasbourg, Rheims, Nancy, and Paris. Autengrubers journey to Paris via western Germany was not only an athletic feat, as he made it on bicycle, but also the first important project involving an artist “on the road,” a painter who, aware of his technical skill and craftsmanship, was determined to seek new impulses in diverse localities and regions. In several of his samesized oil paintings on cardboard, Autengruber offered proof of being a dynamic painter capable of using the devices of colour metaphor and patchy brushwork to evoke a lively representation of a places mood. The expressively decorative character and dark hues of some of his painted scenes relate them to the Prague motifs of Antonín Slavíček and his concept of a street scene with “clusters of colour blots.” Autengrubers pictures from his travels are projections of his search for the life of the “colour freckles” mentioned by Slavíček in a letter of 1908.

Jan Autengruber was not just a talented painter; his other gift was for music. In fact, he loved music as much as he did painting. He played clarinet and violin. In Munich, in 1911, he trained violin taking lessons with conservatory Professor Ludwig Vollnhals who intended “to win him over completely for music.” Not only did Autengruber engage in systematic practice of violin playing; he also portrayed himself as a violinist, painted a still-life with violin, and decorated his own violin with carved patterns.

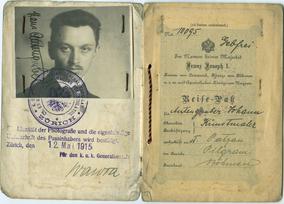

In the second half of November 1913, Autengruber travelled to Italy, thus starting to implement the provisions of the Klaar scholarship which he had been granted for two years, from February 1, 1913, through the end of January 1915. Upon expiry it was prolonged.

In autumn, the artist set out on a voyage leading through Vienna to Venice, and hence to Padua and Bologna, where he celebrated the New Year 1914. He then continued to the south, to Sicily, following in the tracks of the “Grand Tour” travellers, initially set by the illustrious Goethe. In January 1914, Autengruber went to Naples, then to Taormina and Palermo in Sicily. In Messina he was shocked by the sight of the city, still devastated after the catastrophic earthquake of December 28, 1908. He travelled on to Pompeii, Sorrento, Pesto, and to Capri. In March 1914 he left the south of Italy for Rome. There, he produced a remarkable series of drawings of trees, mostly from the Palatine Hill, whose clarity and lapidary treatment leaves undiminished the impression of sharp sunlight penetrating through the canopy. In other works, the painter would use his plein air experience from the Palatine Hill in creating a fictional space wherein he would set, in a way resembling the work of a theatre director, biblical scenes, such as The Flight into Egypt. To him, Italy was thus transformed into biblical landscape. The place which captivated him most, however, was Taormina.

It was in his Italian landscapes, and most notably those of them Autengruber painted in the south, in and around Taormina, that the evanescent, flickering language of colour patches characteristic for his landscapes from the year 1910, gradually changed to an idiom determined by an expressive, summarizing and dynamic metaphor. There, Autengruber came to re- alize much more acutely than he could have done in Central Europe an imperative imposed on him to supersede the virtuoso qualities of painting by a radical expressive dynamism. In May 1915 Italy entered into war. The situation there became precarious for an Austro-Hungarian citizen. Autengruber left in haste for Zurich, to collect a new passport at the Austrian consulate, reportedly leaving behind in his Rome studio some of his works.

During the war, the painter became increasingly preoccupied with timeless biblical motifs, suited better than others for capturing the drama of the time as well as the individuals helplessness in the face of the madness of war. He dealt with the theme of Saint Christopher (Christoforos, the “carrier of Christ”), who had carried the infant Jesus across the river. Autengruber drew Christopher in his sketches for a sculpture he executed in wax in 1919.

In 1914, the artist put down in writing: “...simply and in colour, with no trivial tones, definitely rich yet finely mixed colours, robust modelling, succinctness of form, plasticity, expression!!!” (the last two words underlined three times), “candid large-scale form.” The urgency with which Autengruber became aware of the inevitability of evolving towards “large-scale form” gradually also modified his view of the subjects he was dealing with.

The first surviving composition, where he accomplished not only his pursuit of “large-scale form,” but also that of a “grand theme,” is The Deposition, an oil painting from 1912, of which a black-and-white photographic reproduction has been preserved. From 1914 onward, and most prominently from the time of his Italian visit in 1915, the artisťs drawings, as well as his less copious painterly output, came to feature ever more frequently the motifs of Crucifixion and Erection of the Cross. In terms of composition, they link up with the fairly infrequent scheme with laterally erected crosses, possibly seen by Autengruber in Tintorettos Crucifixion of 1568, from the Church of San Cassiano in Venice. For its part, the motif of the Erection of the Holy Cross was rendered most eloquently also by Tintoretto, in his monumental Crucifixion (1565) in the Sala dellAlbergo of Venices Scuola di San Rocco.

Autengruber heightened expression in several successive paintings of The Erection of the Cross, working with the oblique diagonal of the Cross, hanging from which is, much rather than Chrisťs body, an array of colour rags. The individual figures resemble jets of wildly painted energies, and the scene as a whole is dominated by a chaotic stream emerging from which are the figures, indistinct and evanescent. In these radical works, Autengruber presented himself as an ecstatic Expressionist who, for the sake of enhancing expression, totally abandoned all he had been taught in Munich: namely, a strain of Naturalism toned down by lively Vitalistic technique. The ecstasy and drama of these works also strongly reflects the deepening drama and helplessness of the war years. Between 1914 and 1916 the artist drew a series of variations on the theme of a crouching Saint Sebastian, as well as returning continuously to the theme of Crucifixion. His Saint Sebastian is wedged within the bark of a tree, becoming the tree. This may be the time's only solace: the option of becoming a tree, of turning one's vulnerable and mortal body into a tree.

Salomes sensuous, dramatic and ruthless dance, whose outcome is the severed head of Saint John the Baptist, is with Autengruber as pointed expression-wise as the motif of Crucifixion. The subject was particularly popular with German artists at the turn of the 20th century (Franz von Stuck, Lovis Corinth and others). A significant part in the themes popularization was played by the premiere of Richard Strauss' opera, Salome, in Dresden, in 1905. With these paintings embodying radical, expressively torn dynamic form, Autengruber reached the apex of his art, without exaggeration assuming a position alongside the likes of Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Max Liebermann, or Max Beckmann in his pre-1910 period.

Vojtěch Lahoda, translation Anna Ohlídalová, Ivan Vomáčka